Many

artists reach a plateau and stay there, revisiting the same themes or visions,

never expanding, never stretching, never evolving with their work. And then there are those lucky few artists –

which includes writers, graphic artists, musicians and performers – who

continually grow, develop and stretch their capabilities.

Into

that happy few we must count author, illustrator, animator William Joyce (born 1957).

After creating some of the most beautiful picture books of the 1990s,

Joyce then branched off into his other love, filmmaking, and helped design a

number of memorable films (including Toy

Story), before branching out into production himself. He also started the company Moonbot to make apps, games, animated

shorts – anything, in fact, to which he could harness his storytelling genius. Located in Louisiana, Moonbot is a

human-scale Disney, where talented artists, writers and filmmakers create the

next generation of children’s classics.

His

first love, though, remains books. He

started a series of picture books and prose novels that detailed the origins of

such childhood myths as Santa Claus

and the Easter Bunny called The Guardians of Childhood, and he has

now served up a new original novel with illustrations, Ollie’s Odyssey. It is his

most daring and interesting prose novel to date, and a significant

demonstration of his ever-increasing capabilities.

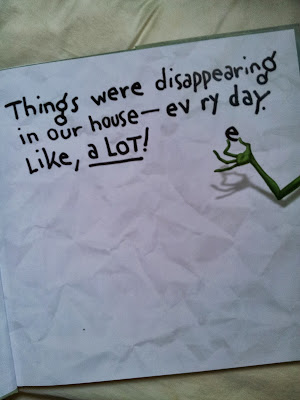

Ollie’s

Odyssey is all about a kid named Billy and his special relationship with his

toy, a ragdoll his mother made named Ollie.

During a wedding party, Ollie is kidnapped by the minions of an evil

toy, the demented clown Zozo. Billy must

sneak out of his home at night and trace his lost friend, a journey that leads

him to a deserted underground carnival, to a confrontation with a horde of

menacing reconfigured toys, and to a final battle

royale led by Ollie and some odds and ends who form a junk army.

In

outline, it would seem as if Ollie’s Odyssey would be just another kid’s

adventure story. But Joyce uses this

framework to write a deeply moving tale about growing up, the inevitability of change,

loss and, perhaps most important, the power of memory. Rather than a stock villain, Zozo has become

twisted through the loss of his beloved ballet dancer-doll. He is a tragic-villain, fully formed and

compelling enough for the most adult fiction.

Similarly, Billy and Ollie fear changes to their friendship as Billy

ages, and Ollie wonders what becomes of toys that are no longer loved. The coming end for their partnership does not

mitigate in any way the love they have for one another, but it does add a

tragic dimension unusual for kiddie fare.

Joyce also talks about resurrection and rebirth during the junkyard

sequence, where now useless bric-a-brac takes on new life and new identity to

help Ollie and save Billy. It is a

stunning juggling act: Joyce has written a profoundly moving and emotionally

resonant novel in the guise of a children’s book.

Just as

Joyce has previously illustrated his picture books with dazzling watercolor

work, and then branched out into both line drawings and computer illustration,

Ollie’s Odyssey tests his versatility with a series of charcoal drawings – a medium

he has not used in his published work before.

The illustrations of Ollie’s Odyssey are unlike those of any of Joyce’s

previous work, and fit the overall emotional tenor of the story

beautifully. Charcoal brings a gritty,

tactile sense to this tale of fuzzy friends and frayed castoffs that would be

missing from glossier modes of illustration.

He also used the paper upon which he drew to great effect, allowing what

would normally be the white ‘tooth’ of the paper to soak up computer-added

color. The book is also beautifully designed

by Joyce with chapter heads in bold red crayon, and different colored papers

representative of different characters and scenes.

As with

much of Joyce’s oeuvre, his latest book can be savored by adults as well as

children. A man who loves popular art immoderately (and wears that love on his

sleeve), Joyce peppers Ollie’s Odyssey with echoes of titans and works that

come before. Attuned readers will catch bits of filmmakers Todd Browning and Lon Chaney, hints of the classic Universal Monsters with a touch of The Island of Lost Souls, a healthy smattering of Ray Bradbury, and shout-outs to

everything from the original King Kong

to Batman Returns to The Magnificent Seven. Indeed, the final image of the book is a

direct rift on John Ford’s mighty

ending for The Searchers … and one

wonders if Joyce is writing for adults who have kept their inner child alive

and well, or if he writes for children who will one day make more adult

connections.

Ollie’s

Odyssey is a bigger, grander, more ambitious book than anything that Joyce has attempted

before, and he rises to the occasion splendidly. It is certainly the finest of his prose

novels, and one cannot but wonder what this protean talent has in store for us

in future years.

While we

are delighted that Joyce has spread his abilities into so many different areas,

it is perhaps in books that devotees get the fullest distillation of his

talents. His written and illustrated

works are the least collaborative of his output, and capture his philosophy

best. That view of life has been

changing and evolving over time – that William Joyce names his protagonist

Billy is surely no accident – and if the man himself can emerge from the

crucible of experience with his sense of wonder intact, what is he not capable

of? And what, he asks, are any of us not

capable of? It’s that sense of possibility,

that childlike sense of limitless adventure, that the world is filled with

things to delight each and every one of us, that is the essence of Bill Joyce.

Ollie’s Odyssey

is highly recommended to kids, old people, and everyone in between.